For decades, Bangalore (or Bengaluru) was known as the “Garden City” for its numerous public parks and even the large gardens of private bungalows. This image of a city full of trees and flowers is one that has persisted with the city’s long-time residents.

And, Lalbagh, Bangalore’s oldest garden, has a special place in the hearts of many a Bangalorean. This expansive botanical garden has an especially interesting past, one that’s closely intertwined with the city itself.

The History of Parks in Bangalore

Thanks to its elevation and mild climate, Bangalore has long been a natural paradise. In her analysis of inscriptions found in the area, ecologist Harini Nagendra1 talks about how the earliest settlements were once surrounded by not only agricultural land, but also dense scrub and jungle.

By the 1600s, when modern Bangalore was founded by Kempe Gowda, the town was still known for “trees thick with flowers and shade [that] lined each home garden,” as seen in one of the earliest descriptions of the city from the 1670 poem Shivabharat by Kavindra Parmanand.2

Parmanad also describes Bangalore as a city of lakes and wells, with wells in almost every house, in public markets, and at chatrams (traveller’s rests).

Even 18th-century rulers Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan were known for their fondness for gardens (though for military purposes, the area outside forts was kept clear of trees).

When the British first set up their Cantonment in the city in 1804, they applied their own ideas of park-planning, which were then used by the City Municipality under the Mysore Maharajas, and later the state government.

The Story of Lalbagh

When the city of Bangalore was founded in the early 1500s by Kempe Gowda, a feudal leader of the Vijayanagara Empire, he and his descendants are said to have3 established four cardinal towers to set the limits of the city. One of these towers was built atop an ancient rock that’s billions of years old (now known as Lalbagh Rock). While the city has outgrown these many times over, the rock is still identified as a National Geological Monument.4

Created by Hyder Ali

Then, over two centuries later, in the 1760s, Hyder Ali, the then ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore, commissioned the building of a 40-acre garden complex near this ancient rock. This roughly rectangular garden was located north of and adjacent to a tank (as seen in maps from between 1760 and 1856).5

It was designed along the lines of Mughal Gardens6 that were popular at the time. More specifically, they were inspired by the gardens of Dilawar Khan (an official of the southernmost Mughal suba, or province, in the Deccan) at Sira.7

Hyder Ali imported plans from across the sub-continent to fill his gardens, including from Delhi, Multan, Lahore, and Arcot.8

However, it was Hyder Ali’s son Tipu Sultan who expanded the gardens, importing seeds and saplings6 of trees from Afghanistan, Persia, Turkey and Mauritius. During this period, the gardens were under the direct supervision of Mohammed Ali and his son Abdul Khader.

Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, a Scottish physician and botanist, visited the gardens around 1800 during his survey of Mysore, noting (in A Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar, 1807) that:9

The gardens are extensive and divided into square plots divided by walks the sides of which are ornamented with fine Cypress trees…..want of water is the principal defect of these gardens for in this arid country everything during the dry season must be artificially watered. The garden of Tippoo is supplied from 3 wells, the water of which is raised by the ‘capilly’ or leather bag, fastened to a cord passing over a pulley and wrought by a pair of bullocks which descend on an inclined plane.

Under the British

After the death of Tipu Sultan in 1799 and the British restoration of the Wodeyars of Mysore, the garden fell under the administration of a number of officers.10

At first, Governor General Wellesley of the East India Company appointed Benjamin Heyne, a medical officer and naturalist, to “the Sultan’s garden at Bangalore” to develop it “as a depository for useful plants.” To this end, Heyne introduced plants that would be used to supplement the regimental messes.

In 1807, the gardens were returned to the Mysore Government, under Major Gilbert Waugh, a keen amateur botanist and EIC Paymaster. He wanted to turn it over to the Company to use as “a supply to British India […] of the fruits etc. of England, China & other Countries”. But this was ultimately unfulfilled, and the Mysore Maharaja turned the gardens over to Nathaniel Wallich.11

Also around this time, gardens began to be called “Lal Bagh” (literally “Red Garden”), possibly due to a profusion of red flowers.8

In 1831, with the deposition of Maharaja Krishnaraja Wodeyar III (and later the minority of Yuvaraja Chamaraja Wadiyar X), the kingdom and Lalbagh came under the purview of the Mysore Commission.11 For a time, it was used for horticultural training under William Munro of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society.8

Eventually, in 1855, it came under the purview of Hugh Cleghorn, a botanical advisor to the Commissioner of Mysore. Cleghorn was against the use of Lalbagh for commercial enterprise, but thought it was perfect for establishing a horticultural garden. It was meant to improve the use of indigenous plants, introduce useful exotic species, and exchange plants and seeds with gardens across India.8

With this goal in mind, Lalbagh was named the Government Botanical Garden in August 1856 by the Mysore Commissioner, Sir Mark Cubbon, and a professional horticulturist (William New) was brought over12 from Kew Gardens to be its Superintendent.

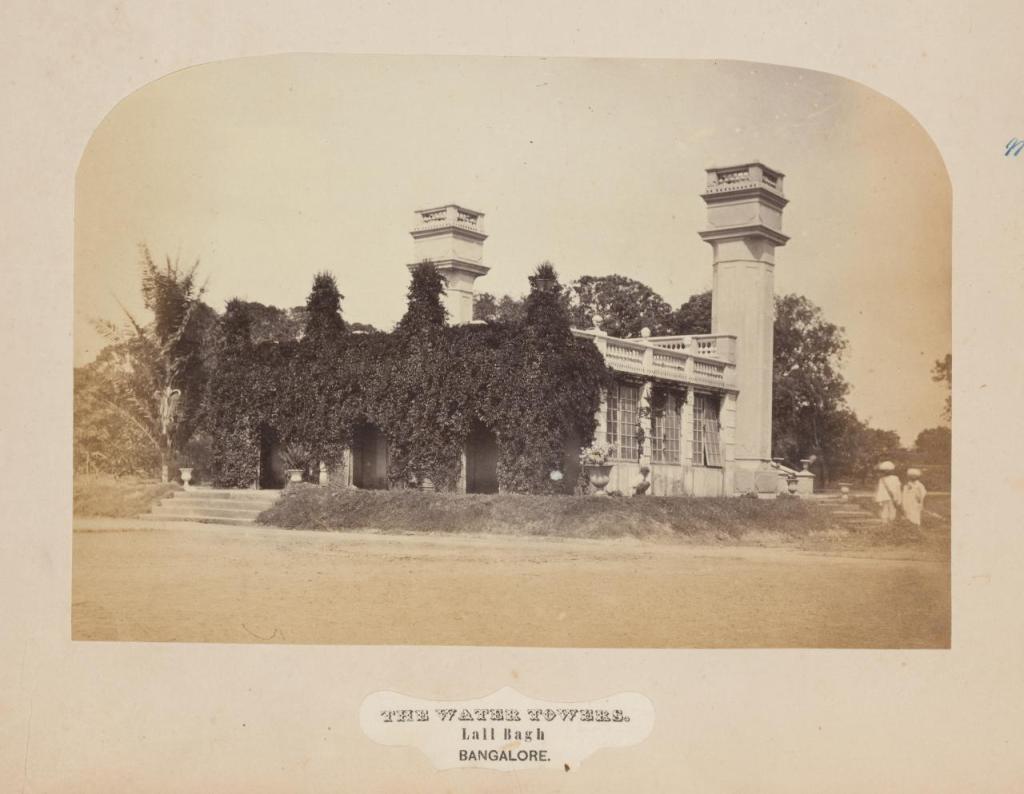

New (s.1858-1873) established greenhouses, a number of residential cottages, a menagerie, an aviary, and a bandstand. His 1861 catalogue of the plants of Lalbagh included both economic and ornamental plants, including cinchona, coffee, tea, macadamia nuts, hickory, pecan, rhododendrons, camellias, and bougainvillaeas.13

He also began the tradition of organising flower shows at Lalbagh, which continues to this day.

Cleghorn’s successor, John Cameron (s.1873-1908), continued these improvements, helped by the newly installed Maharajah of Mysore. Cameron, also from Kew, introduced scientific methods of gardening and a system of experimental cultivation of crops, including varieties of cabbage, cauliflower, turnip, radish, coffee, rubber, and grapes, that were later implemented across the state.14

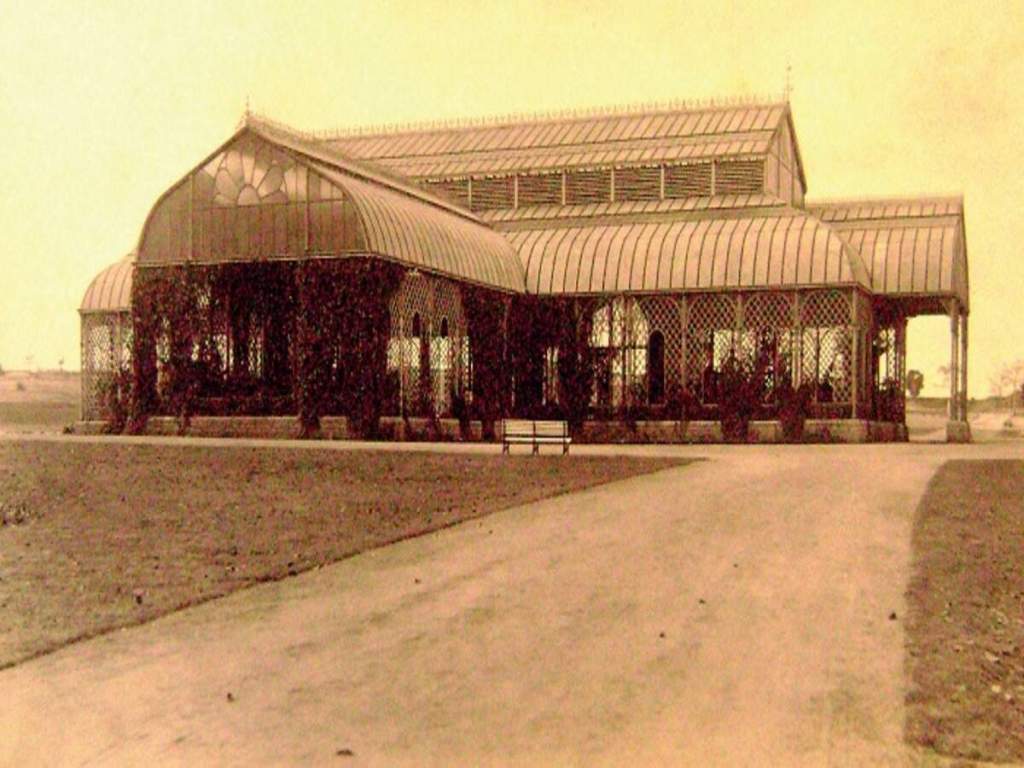

He is also credited with adding a baobab from Africa, a 15 ft high dovecote for 200 birds (in 1893)15, and most famously, the iconic Glass House (modelled on London’s Crystal Palace). Its foundation stone was laid on 30 November 1889 by Prince Albert Victor. It was completed in 1890 (using cast iron from the Saracen Foundry in Glasgow)14.

Cameron also significantly expanded16 the area of Lalbagh to around 80 acres. In 1874, it had an area of 45 acres, but by 1894, the gardens covered 188 acres. His later years were clouded by a plague epidemic in 189817, which led to deteriorating maintenance of the menagerie and aviary.

Cameron retired in 1908 and was followed by perhaps Lalbagh’s most famous Superintendent, Gustav Herman Krumbiegel (s.1908-1932). A German-born and Kew-trained gardener, he expanded the focus of the gardens, especially with regard to garden architecture and landscaping, making them one of the foremost centres of horticulture in Mysore State.

In 1914, Captain S.S. Flower, a science advisor and zoologist, was sent to India by Lord Kitchener to report on collections of animals in captivity.18

He reported that the menagerie included: a court built between 1850 and 1860 with tigers; an aviary; a monkey house with an orangutan; a paddock with blackbuck, chital, Sambar deer, barking deer, and a pair of emus; a bear house and a peacock enclosure.

The first Indian Superintendent was H.C. Javaraya (s.1932-1951), who is perhaps best known for adding an east wing to the Glass House, 19 with steel from the Mysore Iron and Steel Company. He also gradually moved the animals and birds to the Mysore Zoo, with the menagerie finally closing in 1933.20

In Post-Independent India

The last well-known Superintendent of Horticulture was M.H. Marigowda (s.1951-1974). A horticultural expert, who—like his predecessors—had also trained at Kew Gardens, he is famous for spreading horticulture across the newly formed state of Karnataka, establishing as many as 400 farms and nurseries.9

Marigowda also expanded Lalbagh to its current size of 240 acres, and welcomed many famous people to the gardens, including Queen Elizabeth II in 1961.21

After his retirement in 1974, the Government of Karnataka brought Lalbagh under the protection of the Karnataka Government Park (Preservation) Act, 1975, to ensure that its ecological uniqueness was preserved.

What to See In Lalbagh Today

Today, Lalbagh is full of wonderful things to see. Every walk through the park will unearth hidden wonders and long-forgotten gems. Apart from the thousands of varieties of plants,22 Here are some of the highlights that you can’t miss:

Lalbagh Lake – in the south of the park lies the man-made Lalbagh Lake, with its walking trails and even a mini waterfall.

Lalbagh Rock and Kempegowda Tower – atop this ancient metamorphic rock (known as Peninsular Gneiss) is a historic tower built by Kempegowda in the 16th century. As a bonus, it also boasts stunning sunset views.

Glass House – originally built in 1889 in honour of Prince Albert Victor23, grandson of Queen Victoria. Renovated in 2004, today it hosts Lalbagh’s many splendid flower shows.

The Bandstand – when it was first built in the 1860s, it served as a place for a band to serenade promenading visitors with music, and was the original venue for Lalbagh’s flower shows. Today, it hosts a number of cultural shows.

Other Attractions – the old aquarium, bonsai garden, flower clock, hibiscus garden, and more.

Works Cited

- Nagendra, Harini. Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present, and Future. Oxford University Press, 2016. ↩︎

- Iyer, Meera. “Water for Parched Bengaluru.” Deccan Herald, 5 June 2021. ↩︎

- Dr. R. Narayana. “Kempe Gowdas of Bengalooru (Bangalore)”. Volkkaliga Parishat of America (VPA), 2009. ↩︎

- “Peninsular Gneiss.” Geological Survey of India, 21 July 2011 (Archived from the original) ↩︎

- Iyer, Meera & Nagendra, Harini & Rajani, M.B. “Using satellite imagery and historical maps to study the original contours of Lalbagh Botanical Garden.” Current science. vol. 102, no. 3, 2012, p. 507-509. ↩︎

- Bowe, Patrick. “Lal Bagh – The Botanical Garden of Bangalore and Its Kew-Trained Gardeners.” Garden History, vol. 40, no. 2, 2012, p. 228–38. JSTOR ↩︎

- Benjamin Rice, Lewis. Mysore: A Gazetteer Compiled for the Government, Volume I, Mysore In General, 1897a. 1897. Archibald Constable and Company. p. 834. ↩︎

- Bowe, Patrick. “Lal Bagh – The Botanical Garden of Bangalore and Its Kew-Trained Gardeners.” Garden History, vol. 40, no. 2, 2012, p. 228–38. JSTOR ↩︎

- Hamilton, Francis Buchanan. “Papers of Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, 1807 – 1840.” Royal Asiatic Society Archives. GB 891 FBH ↩︎

- da Cunha, Dilip and Mathur, Anuradha, eds. Deccan Traverses: The Making of Bangalore’s Terrain, 2006. Exhibition: Deccan Traverses: The Making of Bangalore’s Terrain (Lalbagh Glass House), 2004. ↩︎

- Bell, Evans (1866). The Mysore Reversion, “an exceptional case” (2 ed.). London: Trübner and Co. pp. 9–12. ↩︎

- Vinoda, K. The Lalbagh – A History, 1760–1932. Department of History, Bangalore University, 1989. Internet Archive. ↩︎

- New, William. Catalogue of Plants in the Botanical Garden, Bangalore, and Its Vicinity. Mysore Government Central Press, 1861. Rare Book Society of India. ↩︎

- Iyer, Meera. “A Jewel in Lalbagh’s Crown.” Deccan Herald, 22 Nov 2010. ↩︎

- Thiruvady V R. Lalbagh: Sultan’s Garden to Public Park. 2020. Bangalore Environment Trust. ↩︎

- Srinivas, S. “History of Lalbagh.” Deccan Herald, 9 July 2012. ↩︎

- Dasharathi, Poornima. “The plague that shook Bangalore.” Deccan Herald,

22 Aug 2011. (Updated 16 May 2020) ↩︎ - Flower, S.S. Report on a Zoological mission to India. 1914. Government Press, Cairo. pp. 40–41. ↩︎

- Iyer, Meera. “Bangalore’s Rock-Solid Lung Space.” Decan Herald, 7 June 2010. ↩︎

- Prasad, S Narendra. “A walk through Lalbagh’s history.” Decan Herald, 23 Jan 2023. ↩︎

- Shravan Regret, Iyer. “Before IT City in Bengaluru, It Was Fruit Basket, Thanks to One Man!” Shravan Regret Iyer, 13 Mar. 2017. ↩︎

- Cameron, John. Catalogue of Plants in the Botanical Garden, Bangalore, and Its Vicinity. Bangalore, Mysore Government Central Press, 1891. Internet Archive, (Uploaded by Cornell University Library) ↩︎

- “The Glass House, Lal Bagh Botanical Gardens, Bangalore, India.” The Victorian Web, 20 Aug. 2010. ↩︎

Further References

- Nagendra, Harini. Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present, and Future. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Vinoda, K. The Lalbagh – A History, 1760–1932. Department of History, Bangalore University, 1989. Internet Archive.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Lal Bagh.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 3 Nov. 2021.

- Sharma, Yashaswini. Bangalore: the Early City: Ad 1537 – 1799. United States, Author Solutions Incorporated, 2016.

- Sharma, Yashaswini. “3.5 Lāl bāgh” Bangalore: the Early City: Ad 1537 – 1799. Author Solutions Incorporated, 2016, pp. (PDF of chapter)